Genre

Audience

Author’s Worldview

Undisclosed

Year Published

2020

Themes

Reviewed by

A.R.K. Watson

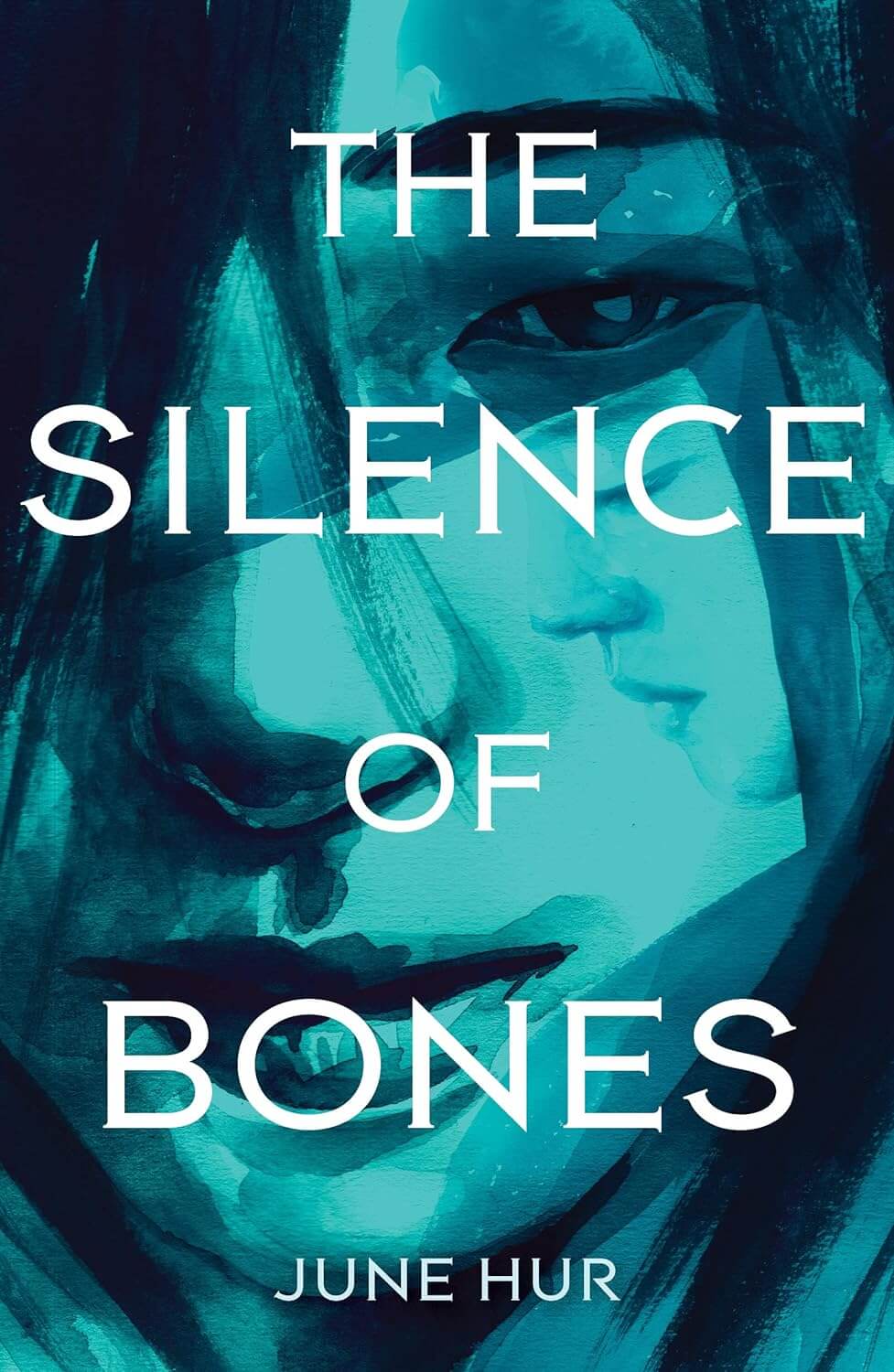

It is 1801 in Korea. Seol is an indentured servant to the police bureau in the capital. She bears the brand on her face of a runaway and remains determined to return home, but not before she can find out where her brother’s grave is. While investigating her own family mystery, Seol comes under the charge of the cold and inscrutable Inspector Han. Together they become embroiled in the mystery of a murdered noblewoman, which soon involves the growing political unrest brewing around Korea’s Southern Catholic political faction.

As a woman in a Confucian society and a member of one of the lower castes, Seol has little protecting her. On the other hand, she has the ability to move around and talk to people without drawing much notice. Inspector Han soon begins to rely on her intelligence and becomes to Seol, her only protection from the intrigues of the capital. But her loyalty is tested when Han himself becomes the primary suspect.

This is a tense and fascinating look into Korean history, especially Korean Catholic history, with saints Fr. Jacob Zhou Wenmo (the first priest in Korea) and St. Lady Kang Wan Sook Columba making appearances and even aiding Seol in her journey. For those who do not know, Korean Catholic history is unique in the world because the Catholicism there was not the product of any missionary efforts. In fact, Korean scholars and noblemen converted by themselves after researching various western philosophies and technologies on their own in an effort to learn more about the world. Koreans then sent their own delegation to the Vatican to request that the pope send them priests. In the meantime, the Catholic church was organized and led entirely by lay people. Fr. Wenmo, a Chinese Catholic priest, traveled in secret to Korea to minister to people there and was able to hide from the government largely because of the efforts of the noblewoman, Lady Kang, who funded and led the church, despite being a woman and a divorcée. However, knowing this history is not required for understanding the central story. Hur does a great job in making this book accessible to the general reader no matter their faith, while also giving a basic education on ancient Korean culture and Catholic history.

I binge read this book in three days, and for someone who enjoys trying to guess a book’s outcome, I was impressed with the amount and quality of plot twists that Hur throws in. Most authors lose a book’s momentum when the reader doesn’t have at least some idea of where the story is going, but Hur knows how to keep readers on their toes.

Although Catholic readers will connect with the story in a unique way, this book is very accessible to any reader of any faith or belief system. The main character herself is not Catholic, or Christian, nor even Buddhist. I was not aware until I read this book, but by the early 1800’s Buddhism itself was out of favor in the culture, being seen as superstitious and backward. A utilitarian sort of Confucianism was the rule of the day. In one chapter Seol visits a Buddhist monastery as part of the murder investigation, and the monks explain how they let their home be a refuge for unwed mothers and orphaned children as an act of charity. There is also a good range of different Catholic characters. Obviously, the real historical saints are good people in the story, but one of the story’s antagonists is also a Catholic whose anxiety about the brewing persecution leads him to act uncharitably. There are sincere Catholic characters as well as Catholic characters who are in the Church for very selfish, superficial reasons. This variety actually ends up making the Catholic persecution more tragic, because Hur is thus able to convey how regular people’s lives were disrupted because of the political machinations of a new queen, seeking to use the persecution of Catholics to solidify her power.

Younger readers may not be ready for the very scary descriptions of torture that the police bureau perpetrates, or for the descriptions of a serial killer who collects the noses of his victims. But if young readers can handle a PG13 movie, they will probably not be fazed by this story.

In light of the pope’s announcement that the 2024 World Youth Day be set in South Korea, and the recent installation of St. Andrew Kim Taegon’s statue in the Vatican, I would encourage all Catholics to read this book and be inspired by the zeal of our brothers and sisters in the East. And as someone who has been living in Korea for four years now, I hope this country will be recognized for the rich pilgrimage destination that it is.