Genre

Audience

12th Grade & Up

Author’s Worldview

Catholic

Year Published

Themes

Reviewed by

A.R.K. Watson

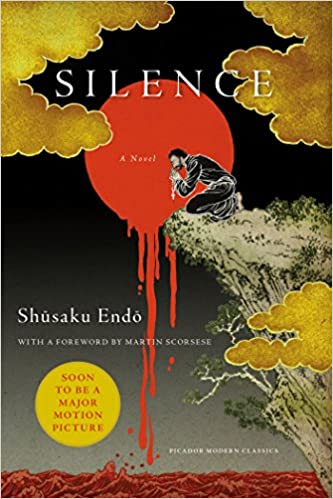

If you are not reading this book in Japanese, if you are not born and bred on the shores of Japan– this book is not written for you. This is not to say that I don’t think everyone should read it (they should) but if you are not a secular or Shinto-Buddhist Japanese you should enter into Endo’s story with the same disconnect as you would entering the house of a stranger; with the understanding that this enviroment is not designed for you, your health, or your convenience. Instead view it with the idea that this house has been built for the habits of another, and you might only gain a great insight and empathy to your neighbor. You might even find something useful in the organizational design to take home and adapt in your own house.

When Endo published this novel he was beginning his career as an author. He lived in a world where Christianity had only been legal for roughly fifty years, meaning that there were people alive who remembered living under threat of death for their faith. He wrote in a country that was wracked with the consequences of the horrors they had inflicted on themselves and others in WWII and was (and remains to this day) completely unready to deal with the horrors it had inflicted on Christians. Endo wrote to a secular Japanese audience that had no remorse for these persecutions, and regarded foreigners like his Portuguese missionary with the same sort of suspicion that Americans regarded Russians at the hight of the cold war. He was never trying to laud the virtue and bravery of Christian saints. He was trying to draw his traumatized culture into a place of empathy and repentance. If you go into this book not understanding this origin, you are subjecting yourself to frustration and confusion. And yet, that is perhaps one of the main values that this book can give a western reader. So much of the world has been touched by colonial influence that spaces that are not built for us are rare, but all the more valuable for the lessons they can teach us.

At the start of the book, in 1639, Japan has just squashed a rebellion of Christian peasants. Fears of European conquest induce Japan to close its borders to the outside world. Anyone found to be a Christian is tortured and killed. Still, the Church sends in its missionaries. But then comes news that Fr. Ferrara, a prominent Jesuit missionary has recanted his faith and is living as a Japanese Buddhist. Two of his students in Portugal, Sebastião Rodrigues and Francisco Garrpe are shocked when they hear this news, and they resolve to travel to Japan as missionaries themselves. They intend to spread the gospel and find Fr. Ferrara: either to clear his name, or to save his soul. As Fr. Rodriguez makes his long, painful journey, traveling across the island in secret, he begins to wrestle with the suffering of the Japanese Christians and, like Job, asks himself, “Why is God silent in the face of this suffering?”

Subscribe to Our FREE Email & Get Weekly Catholic Books for as little as $1

I will not give away the ending of the book except to say that this story falls firmly in the “tragedy” genre, but in a manner that speaks to the undying hope of resurrection- a resurrection that the author himself witnessed as he was a part of the first generations of Christians in his country that were able to experience religious freedom. The sufferings of the people that he writes sowed the seeds of the freedom that Endo’s community could finally celebrate, over three hundred years later. At the same time– three hundred is far too long a time to suffer in silence. This book is as much a meditation of forgivness on those Japanese christians who faltered and recanted their faith as it is the brave ones who accepted martyrdom. But it also shows that there are different kinds of martyrdom and that being misunderstood takes courage as well. In fact it requires a humility that a more violent glorified martyrdom does not.

It is clear why this book is often taught in Japanese high schools as a classic. Reading this story is a deeply intellectual enterprise. It is one of those books that I expect to reread and keep learning from, so be forewarned of the challenge posed by this book when you sit down with it. The imagination and message of this story could not have come from any but a Catholic mind. What impressed me most was how discussing it naturally ushers even the most secular mind into a fruitful conversation about faith and God. Even if Silence does not convert its readers, it leads religious and secular alike into an engagement with the idea of faith that is deeper than usually found amidst the noise of this world.

However, I do not think I have ever read another book so burdened by the weight of conflicting interpretations. A quick search on YouTube will give you a plethora of video analysis claiming that Endo’s masterpiece proves a number of different worldviews–Atheism, Buddhism and Protestant Christianity among them. Given that the author himself was a fervent Catholic Christian—in a society that would have celebrated and even rewarded his conversion to anything else—I seriously doubt that this was the author’s intention and I hope Catholic scholarship will not judge him harshly for how difficult a stumbling block that this story is to the secular mind. The trend of ignoring or erasing the faith of cultural heroes is a common practice even in the West and is especially strong in Endo’s modern Japan where erasure of Christian influence and history was official government policy for nearly three hundred of its most formative years. Even today, this period of Japanese history is often taught in Japanese schools as, at best, a “necessary evil.” Such a hostile cultural climate is important to remember when reading Silence. Endo could never have foreseen how popular his book would become, much less that it would be translated and read by anyone other than a fellow Japanese, and so even though the main character is a Portuguese Jesuit priest, the intended audience is Japanese—an audience that Endo anticipated would misunderstand him. But when it comes to stories—especially Catholic fiction stories—the questions a text prompts you to ask yourself are the source of true wisdom more than the blunt answers it gives.

Subscribe to Our FREE Email & Get Weekly Catholic Books for as little as $1

I must add one more thing. I wrote this review before the pandemic hit. Sometimes I was tempted to belittle, or laugh at what I perceived as the main character’s penchant for drama as he complains to God. After over a year of fluctuating isolations, death and other tradgedies I’ve found this book to become more cathartic and mature than I understood in my first reading. If you are looking for a Lenten reading the might heal some of the stresses of 2020 (and probably 2021) there are few better recommendations than this.

Join Here for FREE to Never Miss a Deal

Find new favorites & Support Catholic Authors