Genre

Audience

Author’s Worldview

Year Published

Themes

Reviewed by

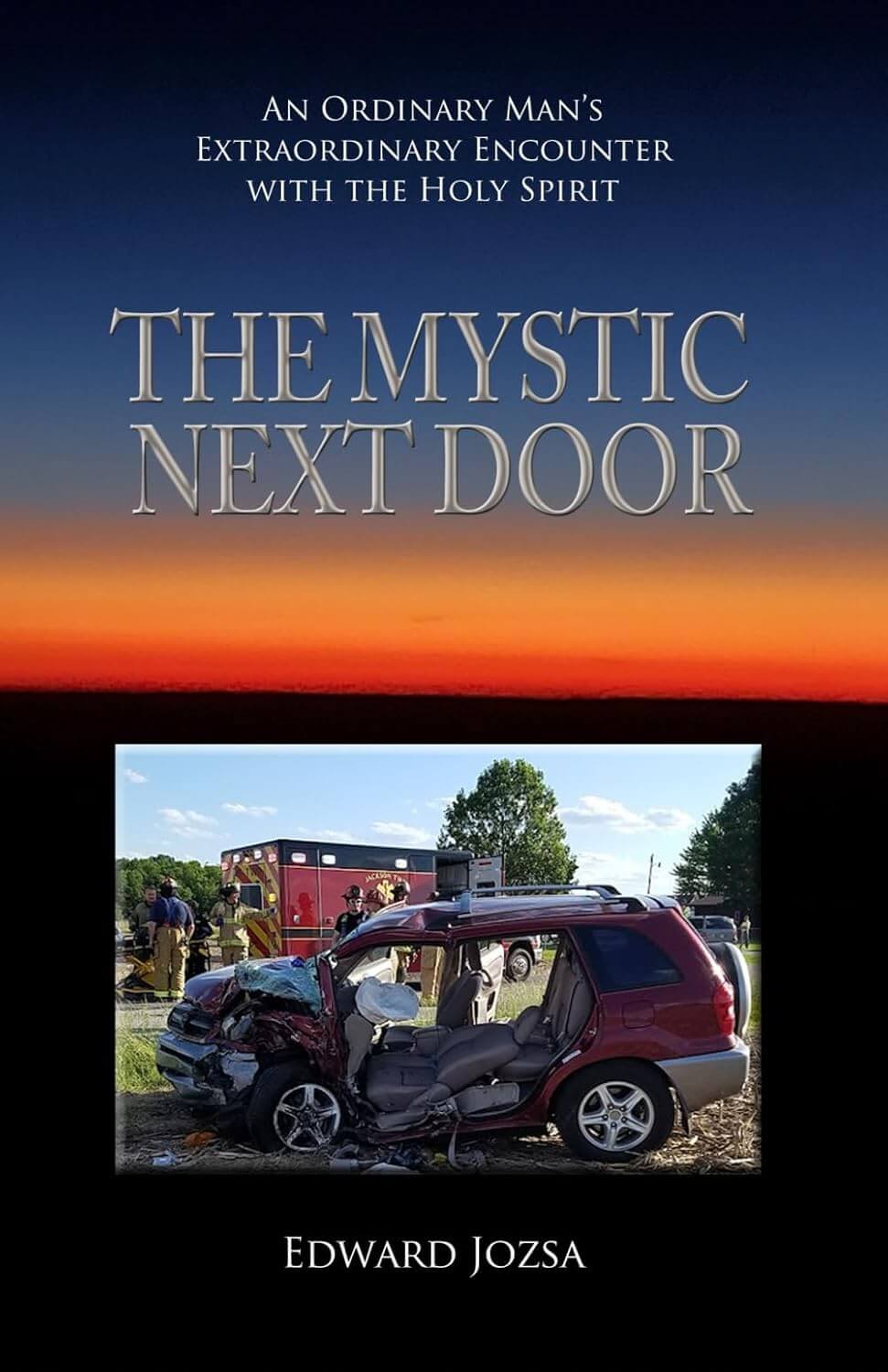

We here at CatholicReads only review books that we can recommend, so the public never hears about the ones we reject. The Mystic Next Door was surely going to be a rejection, I assumed when I glanced at the submission information, because, well, what are the chances that a mystic lives next door? But the first thing that surprised me about this narrative was how succinct, cogent, and precise the prose is. Edward Jozsa is not some strange guy rambling on about his weird dreams. He is a former FedEx pilot who has published a report of his experience of a near-fatal car accident, and of the spiritual visions he received during and subsequent to that event. I don’t have any connection to FedEx other than, like everyone else, occasionally receiving or sending something important that justified the price of the service. And, like everyone else, I understand the high price to be commensurate with the company’s commitment to deliver on time. So, upon reflection, it struck me that a FedEx pilot is extremely unlikely to waste his time or anyone else’s on anything that he does not believe to be essential.

Of course, pilots can go crazy or be brain-damaged, but those people don’t write concise, cogent narratives. And certainly there have been eloquent criminals who persuade people to do things for them. But the only thing Ed Jozsa is asking is that we read his testimony about God’s dramatic intervention in his life. There are lots of people these days clamoring for attention, but this narrative is entirely without self-pity or self-aggrandizement. I should also add that there is no claim to tell us which celebrities are in hell, or when the world is going to end. I don’t have the authority to pronounce on whether Ed’s visions have been personal revelations from God, but there’s nothing in these books that is inconsistent with the historical record or the teachings of the Church.

The Mystic Next Door begins with a description of the car accident that changed the direction of Ed’s life. He spent two and a half hours with his steering wheel crushing his chest, and then another hour in an ambulance while that crew argued with a life-flight helicopter crew about who should transport him to which hospital. Apparently, Indiana state law at the time did not allow a helicopter to transport sedated patients, and the ambulance crew had sedated him before yanking his body out of its crushed position. Ed notes that as a result of his case, state law has since been amended to prevent this sort of situation. So, the second thing that struck me was that a guy who could relate that excruciating experience without casting blame on anybody is a better person than I am.

But the point of the testimony is that Ed also experienced a series of visions. I have read some of the mystics of the Church: St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Avila, St. Faustina, St. Brigid, St. Catherine of Siena, Richard of St. Victor, the transcript of the trial of St. Joan of Arc. There are some basic characteristics of divine communications that we can generalize from these accounts and from those in Scripture:

1) Most important: God does not contradict himself. His revelations do not contradict each other or the deposit of faith.

2) People who receive visions don’t necessarily understand them and sometimes need to consult others for an interpretation. (The most famous examples are the baker and the cupbearer who consulted Joseph the patriarch in Genesis; and Nebuchadnezzar’s vision in Daniel).

3) Visions from God have distinct, detailed elements with precise characteristics (as opposed to natural dreams that morph from one thing into another, hazily and indefinitely).

4) Someone can receive a vision in which he or she remembers that God showed or said things that afterwards are concealed from memory because they are not to be related to others. (Most notably, St. Paul in 2 Corinthians 12 says that there are things that man is not permitted to tell).

5) The vision that the person is taxed with communicating remains perfectly vivid and clear over time (unlike natural dreams, whose impression fades, even if powerful at first).

These are some basic characteristics, but for a really in-depth discussion of this sort of thing, Richard of St. Victor would be the medieval writer to look into. In that era, mystical visions were more openly discussed. For us, living in a materialistic, secular culture that denies even the existence of a spiritual dimension to reality, never mind a God who communicates with us, it is tricky even to broach the topic. For my part, reading through this account, nothing struck me as inconsistent with what I have learned elsewhere. The thing that’s different is that Ed describes what he experienced in contemporary language. The words he reaches for are American words, and we’re not used to talking about anything mystical, in the contemplative sense. Ed himself writes, “I know the countless prayers offered for me made all the difference and may indeed be the reason God bestowed such awesome blessings on me.” He also writes that at the time of this experience, “I had a profound knowledge and understanding of several ultimate truths, and I understood that these truths are universal to us all.” For better, for worse, those ultimate truths had to do with realizing that, despite being a good man by ordinary standards, God was requiring him to undergo a process of sanctification.

The second set of experiences, presented in Triumph of the Cross, occurred six years later, when Ed agreed to participate in Operation True Cross, “a 4,500–mile walk across the country, carrying a relic of the True Cross as a form of reparation for the sins of our nation.” He agreed to participate even though, due to his severe injuries, he was normally only able to walk a maximum of one mile without collapsing. But during his segment of the OTC pilgrimage, he ended up walking six times that long. He also experienced a second series of visions, as well as providential encounters with other people. The message of Triumph is a continuation of the earlier Mystic in that Ed feels “compelled to help awaken those who are asleep, to introduce a spark into souls so that the Holy Spirit may breathe on them and grow that tiny spark into a blazing fire for the Lord.”

This testimonial does not propose any new teaching for the reader who is familiar with Catholic theology. But it will certainly make you reflect on the state of your own soul. As an aid to an examination of conscience, it makes for a vivid change from abstract discussions of general principles. And what I especially appreciated was the no-nonsense language of the narrative, which is entirely free from the sort of cloying, saccharine, and cliché-infested prose that makes so many devotional books a punishment to read. With Ed’s testimony, you can expect to get a gripping sense of the urgency of taking stock of your own spiritual state. Heaven is real. And, like it or not, so is hell. Readers who have an interest in personal revelations will find this testimonial intriguing, but really the mission of the narrative is faith formation in a broader sense, especially sanctification as a process that leads beyond one’s own spiritual development to helping other people in their struggles.