Genre

Audience

Author’s Worldview

Catholic

Year Published

2022

Themes

Reviewed by

Corinna Turner

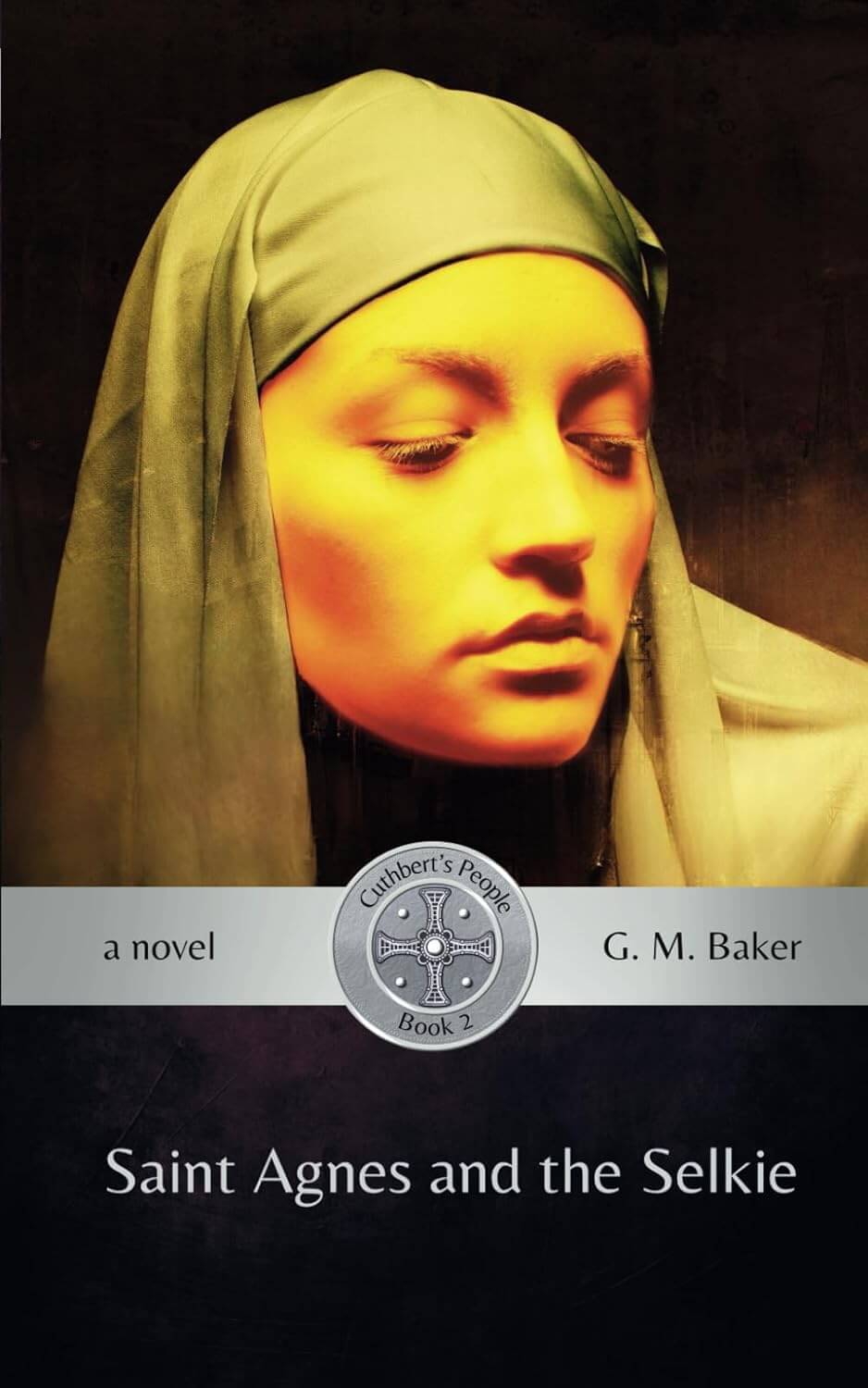

Mother Wynflaed of Whitby Abbey is not supposed to have favorites, but when a girl comes from the sea, too frightened to speak, she quickly comes to feel for her as for a daughter. Everyone who meets ‘Agnes’ falls in love with her—including the young king of Northumberland, Eardwulf. But is the beautiful, traumatized girl a threat to the community?

This is the second book in Baker’s Cuthbert’s People series, continuing the story of Elswyth, and it would be best enjoyed by those who have read book one, The Wistful and the Good (although it would not be impossible to begin with this one).

One of the real strengths of Baker’s fiction for me is his level of historical accuracy—by which I don’t mean that he has every bobbin, spindle, and broadsword correctly named. As he points out himself in the afterword, so little is known about both the events and lifestyle of 8th century Britain that any author will have to invent many details (which he does very well). But he is unusually accurate to historical attitudes and preoccupations in a way that many modern authors of historical fiction are not. This makes his fiction both refreshing and fascinating; a real glimpse into the minds of the past. Nothing is sanitized to suit modern sensibilities.

One example is in the way both king and abbess and everyone else completely accept that it is necessary for a king to wage regular wars on neighbors, otherwise the system of government will not work and his rule will fail, to the detriment of all in the kingdom. Yet, how to be simultaneously a good king and a good Christian is an issue that preoccupies young King Eardwulf and makes him such an interesting character, and his conflictedness rings very true. The influence of Christianity in 8th century Britain was increasingly strong and, inevitably, thoughtful people would begin to become keenly aware of the contradiction between the war-like culture and system of government inherited from pagan times, and Christianity, with its high ideals and demands. According to Venerable Bede (writing a little earlier) several kings even resigned their thrones and went on foot pilgrimages to Rome at the end of their lives, seeking to atone.

Another example is that, in this period, everywhere, from castles to manors to abbeys, there were slaves to do the manual work, and therefore Whitby Abbey owns slaves. The characters express no anachronistic hang-ups about this—it is simply part of the frame-work of their lives. There is even a brief exploration of the medieval idea of everyone having a place and a task in society, based on the parents they were born to.

As with the first book in the series, it is necessary to caution fans of romance that this is not, despite first appearances, any kind of classic romance. There is a strong romantic thread to the plot, but expectations of a satisfying romantic conclusion will be dashed to the deepest depths. In short, this is not a book for readers looking for a light and happy historical tale. This is a serious read, with grave consequences to the characters’ decisions, and there is no glimmer of light at the end of this.

One of my favorite aspects of Baker’s writing is the way he works interesting snippets and discussions about theology, historical attitudes, and even characters’ psychology into the books very naturally. For example, when Abbess Wynflaed is reflecting to herself:

“The actions of a loving and just father are often mysterious to a child, even if that child does not doubt the father’s love. She did not doubt that [God’s] love, but took assurance from it for her soul alone, not for her earthly possessions, nor the earthly peace of her estates, nor the comfort of her body.”

However, if I have one criticism of Baker’s series, it is that although he often gives intellectually satisfying glimpses of Christian thought, a sense of joy is lacking. We see a glimpse of providence, as God saves many innocents as a result of what was probably, from a character’s personal point of view (and even from the point of view of the good of the kingdom) a previous poor decision, but the overall impression is of characters blowing utterly helpless on the winds of fate—and the winds are not kind. This is, again, very authentic to the period, when the majority of people lacked even the illusion of control over their own destiny that a proportion of the world’s population enjoy in modern times. But some readers may begin to wish that Elswyth could just for once ‘catch a break,’ as the saying goes. A faint but not unrealistically elusive sense of providence saves the book from presenting life as merely “miserable, brutish and short” although it is a close-run thing.

Although book one is told almost entirely from the point of view of Elswyth/Agnes, this book is largely told from the point of view of Abbess Wynflaed, which underlines the fact that this is not a YA series despite the age of the protagonist of book 1. Mature teen readers will probably benefit from the book, all the same. However, as with book one, there is frank discussion and sometimes portrayal of sexuality and sexual matters, so parents may wish to pre-read (although it is a lesser preoccupation in this second book).

Fans of serious historical fiction who are happy with a significant romantic thread will enjoy this book. Despite the abbey setting, most secular readers with an interest in the period will probably be as engrossed as Christian readers, unless they have a strong aversion to any Christianity (in which case they are reading about the wrong historical period!). Protestant, and especially Catholic, readers are likely to particularly enjoy the abbey setting and the book’s authentic-to-the-period preoccupation with issues of morality and faith.

This book is not appropriate for anyone who needs a happy ending. For other readers, it offers a rich, realistic journey into the past.