Genre

Audience

Author’s Worldview

Year Published

Themes

Reviewed by

Throughout the nineteenth and into the early twentieth century, as people were increasingly moving out of their ancestral communities into new towns and cities that grew up with the industrial revolution, mass entertainments, such as Blackwoods Magazine and the music halls were eclipsing the ancient stories and songs that had been passed down for generations. A number of folklorists set out to collect the old songs and stories before they were lost forever. Much of the folk song tradition would have been lost without the likes of Francis James Child and Helen Crighton, and most of our fairy tales would have been lost if not for the Brothers Grimm and Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912), a Scottish folklorist who is most well known for his series of “fairy books” in all the colors of the rainbow, beginning with The Blue Fairy Book (1889), which should still be on every child’s bookshelf today.

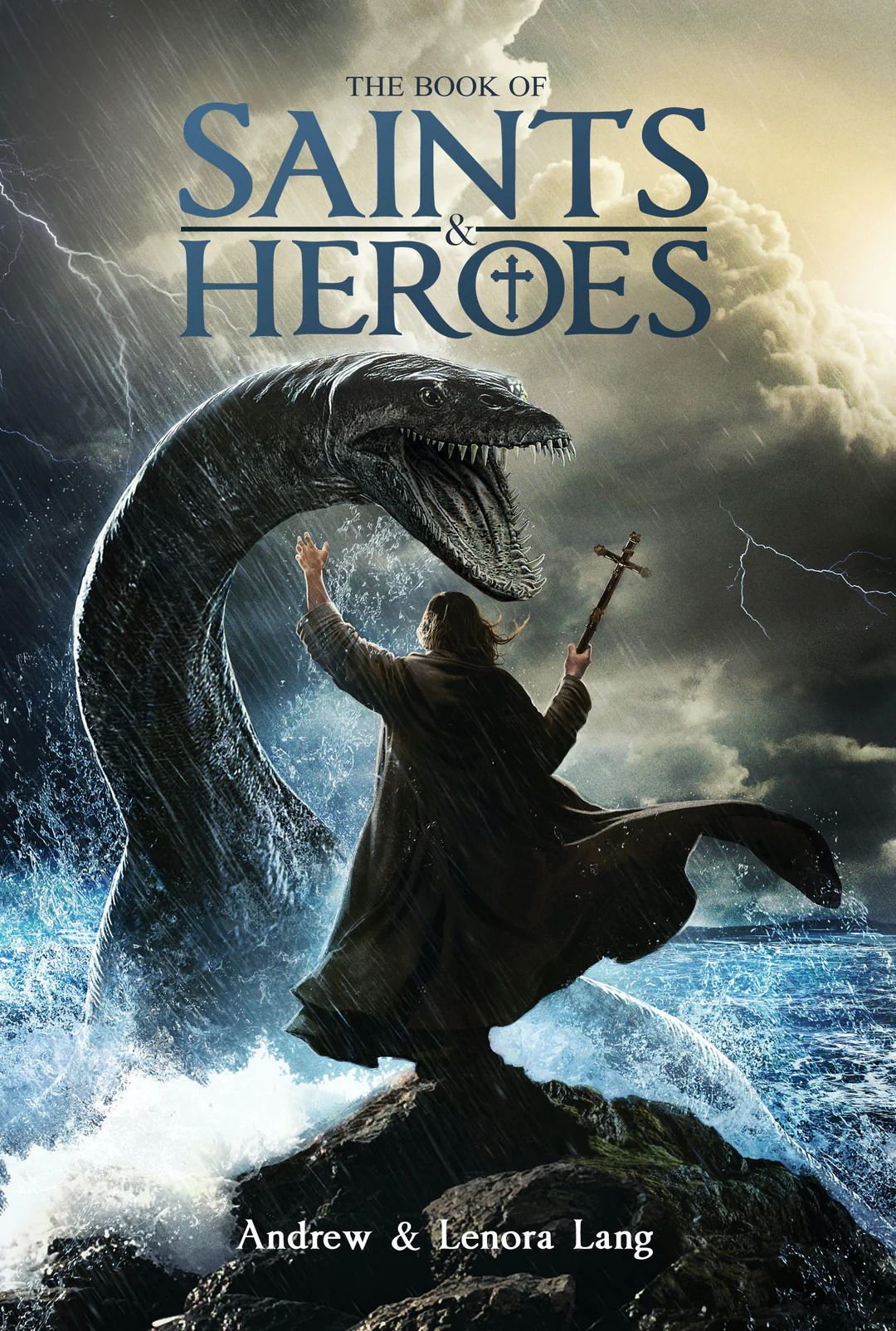

With new media constantly gobbling up more and more of our attention, the work of preserving stories does not end, so it is very welcome that Voyage Comics has chosen to preserve and reissue one of Lang’s last and relatively unknown works, The Book of Saints and Heroes, which relates the stories of a number of great saints, from St. Simeon Stylites to St. Jerome, to St. Cuthbert, to St. Margaret of Scotland, to St. George and the Dragon.

It is important to remember in approaching this book that Lang was a folklorist, and therefore his interest was in the preservation of stories. He was not a hagiographer, setting out to edify his readers or exalt his subjects, nor was he an historian bringing a critical lens to the stories he was retelling. His concern was to tell the story as it has been told down the ages. For instance, in the chapter of St. George, he says:

There are a great many stories about him, of the horrible things that he suffered, and the wonderful and quite impossible things that he did, and he is often mixed up with (a wholly different) George of Cappadocia, who was a bishop and a heretic. But though our George’s sufferings for the Christian faith were exaggerated, and his marvellous deeds a fairy tale, there really did live once upon a time a man who grew famous as one of the Seven Champions of Christendom, and when you have heard the stories about him you can choose which of them you would like to believe.

The same is true of all the stories presented here. You can choose which of them you would like to believe. Though Lang does occasionally comment when a story departs clearly from known history, for the most part the stories are told without comment or critique. Lang, does, however, as a good folklorist, comment on the literary styles employed in some of the stories. Thus he says this of the tales of Irish saints:

In reading the lives of the Irish saints we are amazed and almost confused at the number of wonderful things told about them. The Irish are always fond of marvels and of turning every-day events into a story, and when they began to tell about their holy men and women, they were not contented unless they surrounded them with strange signs, and gave them gifts and powers beyond those of common people. This is the reason that every Irish saint is a worker of miracles from his cradle, and that prophecies showing his future greatness attend his birth. A saint would not have been a saint at all in their eyes, if he had been a baby like other babies, so his father and his mother and even friends at a distance see visions concerning him, and one person repeats the tale to another and, like most tales, it grows with the telling.

For a reader wishing to study the saints, therefore, this book will function better as a starting point than as an end point. But as a starting point it will work very well. The stories are clear and well told, full of incident and no small amount of adventure. But more than this, they offer an insight into the way in which the lives of the saints have influenced Christians of many times and places, how they thought about them, and the lessons our forebears sought to learn from their virtues. If the value of studying the saints lies in the example they give us of Christian living, understanding who our forebears in the faith looked to for inspiration is a useful element of our own study.

As someone interested in folklore and fairytales, I found the book fascinating in other ways as well. The book is written in simple, clear language, and often includes comparisons to things of Lang’s time to help the reader understand things from the stories. In most cases, these comparisons seem as ancient to the modern ear as the things Lang is seeking to explain.

We all know the sad story of Edgar’s two children, Edward the Martyr, and his half-brother, Ethelred the Unready.

No doubt this story was widely known among educated Victorian children, but I think one would have to seek far and wide to find one who knew it today. Lang’s Victorian mores also come through in more than one place, such as in this comment:

Edwy was only fifteen, and had not the talent for governing which marked most of the kings of Wessex. Like many people weak in character, he was very much afraid of being thought to be influenced by anyone; and Dunstan, who was used to being consulted on every occasion by the two former kings, had little patience with his youth and folly.

Another example is his willingness, then universal, now virtually forbidden, of making comment on national character:

The peasants, like all Saxons, were heavy drinkers, and, when drunk, very quarrelsome.

But other than providing occasional bits of amusement, none of these remarks detract from the enjoyment or usefulness of the text. Rather, they provide a kind of dual window into the past, for not only do we have the stories of the distant past preserved, but also the storytelling habits and manners of the Victorians as well. This is instructive, because it lets us see how the stories of one age are interpreted and filtered by another age, which should serve to remind us that our own age also has its particular ways of filtering things and telling stories. Ours will probably look as quaint a century from now as the style of the Victorians seems to us. (This, I feel, is a sentiment that Andrew Lang would very much agree with.)

Looking further back into the storytelling styles of these stories of saints and heroes, we can see a number of similarities in the structure of the stories. It is not just among the Irish that the saints are given exceptional childhoods. Many other saints are said to have been either prodigies in sport or else pious from an early age. Almost all seem to have suffered a period of severe illness. Many had some form of special rapport with animals. Most were rejected by their families or communities. Most seemed to have worked themselves near to death, and most seemed to have had foreknowledge of their deaths. Which of these are actually the common traits of saints and which are simply the common tropes of saint stories is a subject that might invite further study. Indeed, one of the beauties of this book is that it everywhere invites the reader to go further in investigating any question on which they are curious. It is, as I noted earlier, a wonderful starting point for many kinds of study, as well as being an enjoyable read in its own right.

Despite its Victorian storytelling style, in which the narrator frequently comments on the story he is telling, The Book of Saints and Heroes is an easy read. (If you can handle this style in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, you can handle it here.) The stories are written for children, but because they are written by a Victorian, they are written with a much higher level of expectation of the child’s ability, education, and attention span than any modern children’s book, and adults will not feel talked down to.

I can find no information on Lang’s personal religious opinions, but in this case it doesn’t matter, since he is simply collecting and retelling older stories with an eye to their preservation and transmission. The book does not claim that the stories are true or that they are false, only that they were the stories that were actually told. For this reason, the reader’s own religious opinions should not hinder their enjoyment of the book. Christian readers are, of course, more likely to be interested in the stories of saints. But secular readers who are interested in folklore, or simply in a good yarn, will find much to enjoy here.