Genre

Audience

Author’s Worldview

Year Published

Themes

Reviewed by

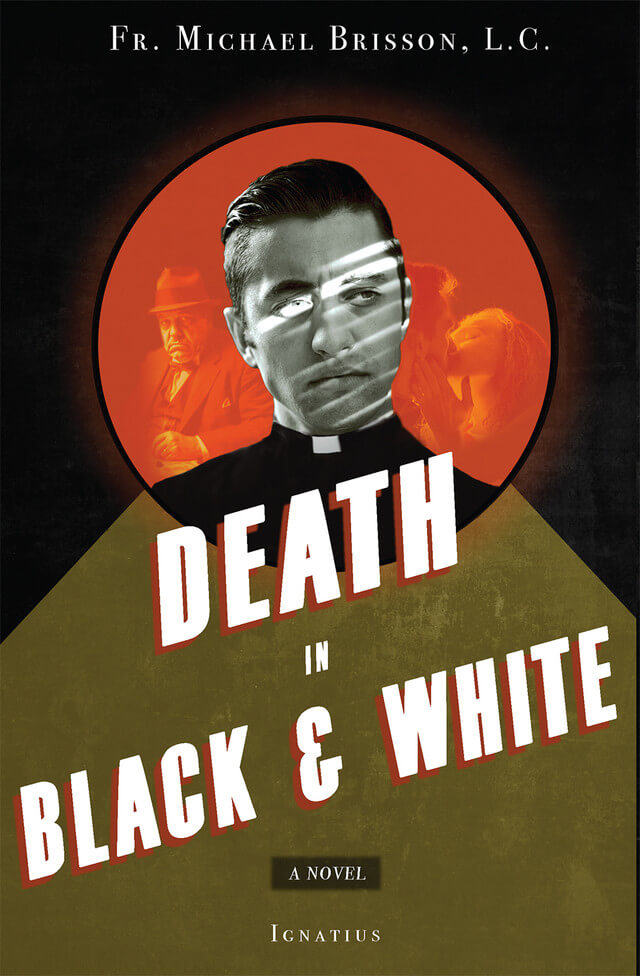

A sub-genre has developed in mystery novels with protagonists who are priests. G. K. Chesterton’s Fr. Brown is the venerable prototype, and all of these that I am aware of have been in that British sleuth tradition, solving whodunits. There are also a few priests who have been English-language novelists. But to my knowledge, Fr. Michael Brisson is the first priest-novelist to give us a priest-protagonist, Father Hart, who tells his own story as a Philip Marlowe-style noir narrator. This is not the sort of story where the resolution of the mystery is going to resolve the underlying issues.

Father Hart, the protagonist of Death in Black and White, is an American-style ordinary guy who finds himself engulfed in increasing depths of crime and corruption. He is, at the outset, a painfully innocent and well-meaning young priest whose upbringing, vocation, and training have in no way prepared him for the sordid and disturbing facts of life and death in the parish to which he has been assigned. Readers who want to keep priests on pedestals will probably not like Father Hart, because he is in every way an ordinary man, susceptible to ordinary temptations, including sexual temptation—except that he has a vocation to the priesthood.

Although Father Hart is perhaps disappointingly unheroic and unsaintly, he is not an evil man. Quite the contrary: he is trying very hard to be a good man and a good priest, and he assumes that others share this fundamental sincerity. He is terribly naïve, and some of the situations he finds himself in are quite funny and believable, as aspects of ordinary parish life. Very soon, however, the narrative plunges him into a grim and disturbing dilemma, when he is abducted by the Mob and required to hear the last confession of a gangster whose boss has sentenced him to death.

It’s at this juncture that we start to experience the underlying worldview of the story: that the eternal death of the soul is worse than the physical death of the body. The story also drives home the Catholic faith that God does forgive all the sins that we confess, no matter how bad. But even readers who believe these tenets of the faith are probably not accustomed to watching the consequent choices unfold. We do after all usually attempt to save the body as well as the soul, and Father Hart’s helplessness in this regard will be just as disturbing for most readers as it is for him. Father Hart has no particular strength, intelligence or courage. His reactions and thought processes are just what any ordinary person’s would be, if thrust into the bizarre situation he finds himself in.

But then it gets worse. Father Hart starts to realize that he is not only up against the inveterate brutality of the Mafia. The clergy too is infiltrated with corruption, and he doesn’t even know exactly who among his acquaintances is colluding with organized criminals. Worldly-wise readers may figure out the answer before Father Hart does, and in fact the most difficult thing about this story is just how trusting and easily deceived he is. Throughout the story, I found myself thinking of Chesterton’s remark, “Evil always wins through the strength of its splendid dupes; and there has in all ages been a disastrous alliance between abnormal innocence and abnormal sin” (Eugenics and Other Evils). The really important trajectory of this narrative, and the one that stays with you, is Father Hart’s journey from this abnormal innocence, through betrayal, failure, and a genuine attempt to fight evil, to what hopefully will be a sadder, wiser condition that will make him a more sympathetic priest. There is a sequel in the works, and I very much hope to be able to read it. I think I will like Father Hart much better as a priest who has himself suffered a failure to live up to his own ideals–without, however, losing his faith or his sense of vocation.

There is always a femme fatale in a noir-style novel, and Death in Black and White fulfills this requirement of the genre, but with an intriguing and even endearing twist at the end of the story. The most satisfying aspect of the narrative is not that Father Hart finally figures out the truth. Rather, what is satisfying is to read a story where the priest-protagonist is an ordinary man with no superlative qualities and no greater sanctity than anyone else, who must himself undergo a process of trial, failure, and repentance. Although the tone of the narrative is on the surface quite lighthearted, corresponding with the original optimism and innocence of the protagonist, it does not leave us with facile solutions to intractable problems. This is a novel that explores what it means to be a priest, in a world where the only people who still seem to have a sense of the sacred are, ironically, the criminals. It also gives us a hard, straight look at the 21st century Church, neither sentimental nor cynical. In the end, the incongruency between evil, corruption and betrayal and ultimate optimism based on faith in Christ is the most impressive juxtaposition within this novel. Granted, you may want to throttle Father Hart at various moments, for the sheer dumbness of some of the mistakes he makes. But the story will also make you grapple with the question of whether you really do believe in “the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.”