Genre

Audience

Author’s Worldview

Catholic

Year Published

1928

Themes

Reviewed by

When Jacques Maritain met his Russian Jewish girlfriend, Raïssa, at the University of Paris, both were atheists, and they were so convinced of the absurdity of existence that they agreed to commit suicide, if within a year they could not find a reason to live. Jacques had been raised by his anti-Catholic mother, who was in a Lutheran phase when he was born, so he was baptized Lutheran. His parents had been one of the first couples to divorce, when divorce was legalized in France in 1884.

Attending the lectures of Henri Bergson convinced Jacques and Raïssa that truth could be known and was not determined by material phenomena. Then Jacques’ good-for-nothing, dilettante Catholic father committed suicide, leaving behind a note to say that, having tried everything else, he was trying death. At that point even suicide became ludicrous, and the couple, now married, decided to seek out Léon Bloy, who became their godfather when they joined the Catholic Church in 1906, to the consternation of both of their families and most of their friends.

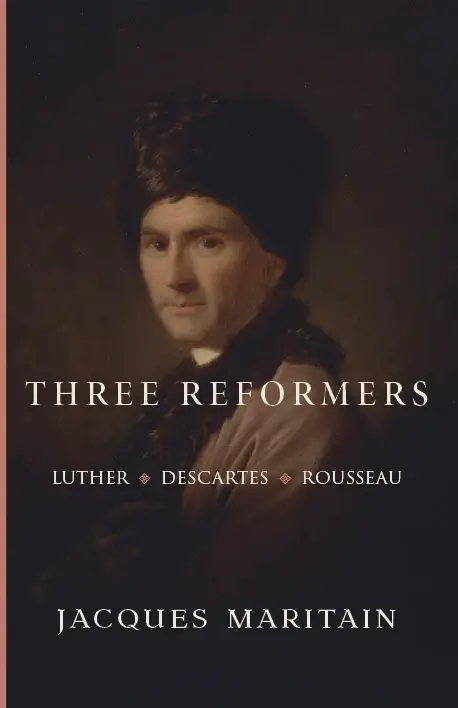

Three Reformers was first published in France in 1925, but Jacques had been lecturing on the topic as early as 1914, when at the start of World War One he began to grapple with the causes of European self-destruction. By then the couple had discovered the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, in which they saw an integrated paradigm of the human person living harmoniously in society, dependent on the Source of being. Three Reformers analyzes the philosophical influence of Martin Luther, René Descartes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau on Western culture, from the perspective of the Thomist philosophy that they rejected. Maritain’s basic thesis is that Western modernity consists of an unraveling of the integrated Christian paradigm that used to hold together, before the strands were peeled away from each other into competing segments. Jacques dedicated Three Reformers to his mother, and among other things the book explains why, having actually studied Martin Luther as an adult, he found he could not be Lutheran.

Jacques Maritain was a philosopher, not an historian, and in selecting Luther, Descartes and Rousseau as the “Reformers” of Europe—the title is sardonic—he wants to elucidate “representative types of the spiritual principles” that define Western societies. Maritain only briefly comments on the general corruption of the Renaissance-era Church and remarks in passing that the Augustinians in the monasteries were opposed to the Scholastics in the universities long before Brother Martin started burning books. What interests him about Luther is his success in defining faith as opposed to reason—such success that, downstream from Luther, everyone still today, Lutheran or not must reckon with this opposition as a given. And yet, before Luther, the Christian philosophical paradigm had been that faith and reason inform each other harmoniously.

Maritain describes Luther as “gifted with a nature at once realistic and lyrical, powerful, impulsive, brave and sad, sentimental and morbidly sensitive. Vehement as he was, there yet was in him kindness, generosity, tenderness.” Luther received a mediocre education which left him with a garbled view of Scholastic philosophy. He became a monk in order to feel the presence of God but was disappointed in his experience of the religious life.

Maritain’s analysis of the philosophical problem of Lutheranism is that he “confounds two things which ancient wisdom had distinguished…individuality and personality.” Before Luther, Christian philosophy distinguished persons as beings with immortal souls, whereas individuals could be any discrete entities, with or without souls, down to the undivided atom. So, an individual is a part of a whole, whereas the human person, created in the image of God is itself a coherent whole made to live in relationship with other wholes. By making the human being merely an individual, modern society gets rid of the personal relationship of each human being with God. Therefore each individual is merely a fragment of society—which is not a whole either, but merely an aggregate of fragments.

By contrast, according to Thomist philosophy, persons in society should subordinate themselves to the common good—but each person in a state of grace is also the dwelling of the living God. Human authorities receive their jurisdiction from God and are therefore accountable to God to ensure that their subordinates can live moral lives. The ruler’s command must be disobeyed if it contradicts God’s command, but so long as there is no contradiction, Christians are to obey the human authorities under whom they find themselves placed. The laws of human societies derive not from the will of individuals but from the justice of God toward persons. Rulers must pursue temporal good with respect for its subordination to the spiritual and eternal good to which every human person is ordered.

The irony is that Luther the Augustinian was exercising his personal responsibility to protest the religious corruption of his day. But when he rejected both human authority and rational analysis, he walled himself into his own interior turmoil, leaving himself no possibility of aid from merely human sources. Maritain compares Luther in his melancholy to King Saul in the Old Testament: anointed by God, yet tormented by evil impulses that he knew to be evil but did not resist. Like King Saul, Luther found solace in music and said that the devils fled when he played his flute. Maritain calls Luther “the first great Romantic,” because of his total reliance on subjective feeling and total rejection of the rational ordering of life characteristic of the Catholic tradition.

Luther’s anti-intellectualism was not just a hatred of Scholastic philosophy. He also rejected the Anabaptists’ positive view of reason as a “torch” to light our way. Nor did his views soften over time. In his last sermon at Wittenberg he thundered: “’Reason is the devil’s greatest whore; by nature and manner of being she is a noxious whore…eaten by scab and leprosy who ought to be trodden underfoot and destroyed….She is, and she ought to be, drowned in baptism….’” After Luther, to think logically was already to contradict faith, since any exercise of reason was evidence of a resurgence of the unbaptized, unregenerate self. From a philosophical perspective, Luther is the source of modern voluntarism, the exaltation of the will against the intellect.

By contrast, Thomist philosophy describes two complementary activities in every mind: the will, occupied with the good of the subject; and the intellect, which is turned outward, toward the object observed. The function of the will is to take action toward the good. The function of the intellect is to seek truth. If people are merely volitional, they disregard truth. If they are merely intellectual, they disregard goodness. So you can have virtuous people who are not clever enough to survive. And you can have clever people who are not virtuous enough to do the right thing. The integrated person should exercise both the will and the intellect in harmony with each other. On a societal level, ideology that emphasizes the will leads to subjectivism. Ideology that emphasizes the intellect leads to mechanism. Maritain traces Western subjectivism back to Luther’s exaltation of the human spirit against authority. After Luther, the interior energy of the individual is set against conventions imposed from without. With no possibility of an intellectual bridge between the self and the other, human freedom becomes an opposition between oneself and everything else.

René Descartes represents the opposite extreme. Maritain shows how Descartes’ conception of human thought derives from Aquinas’ conception of angelic thought. This “angelism” of Descartes supposes human cognition to be independent of surrounding objects and unmediated by the senses, as though human beings were (like angels) pure spirits, no longer the “rational animals” of Thomist philosophy. Aquinas had said that angels, unlike men, do not derive their ideas from things but have them direct from God. Then Descartes came along and described human intellect as intuitive, innate and independent of things—no longer differentiated from angels by embodiment in time. Descartes aimed to free philosophy from the burden of discursive reasoning. But the result is that the operation of interior conviction of truth no longer belongs to an intellect whose God-given function is to apprehend truths—but to the will, which must agree that an idea is an accurate representation of a truth.

Whereas Aquinas had described the intellect and the will as distinct operations, the now disembodied intelligence of the Cartesian mind perceives and judges simultaneously, in one simple act, no longer progressively actualizing knowledge through a logical train of thought. Whereas in the Thomist paradigm, the intellect apprehends the observed object and leaves the will to judge it separately, the Cartesian judging-intellect makes a model for reality to fit into. Ideas now represent facts. The mind cannot simply apprehend something real but is sealed off from reality, no longer able to respect sense perceptions.

Cartesianism disowns the essential dependence of our present knowledge on our past: our human condition as physical beings in time. Descartes does not understand the essential function of time in bringing human cognition to maturity and wants the human judging-intellect to apprehend everything instantly, like the angels. There can be no varying degrees of certitude in this angelist paradigm. Downstream of Descartes’ enormous influence, the result has been the devaluing of all knowledge that is not mathematically evident. Science became mechanistic. Dissociated from sense perceptions, the judging-intellect is left to itself to grasp existence from pure ideas.

The Cartesian paradigm brought about a radical change in the notion of intelligibility—what is considered a valid explanation. Downstream of Descartes, to be intelligible is to be capable of mathematical reconstruction. The mechanical explanation becomes the only legitimate one. Only mathematical ideas are intellectually self-evident, and that’s why, in the post-Cartesian world, mathematical models are used to describe everything else. Anything that cannot be modeled in this way is discarded. It is no longer possible simply to observe and describe. Rather, scientific inquiry must impose a model onto the field of observation. These models often violate reality in order to make observations fit the desired theoretical presupposition.

Cartesian angelism results in a retreat of the mind into itself. The yearning for absolute freedom from physical limits ends up reducing the sphere of thought to the very narrow range of ideas that can be apprehended intuitively. The Cartesian mind does not need to be taught but proceeds by instantaneous discovery. So human beings do not need each other. Disembodied intellects do not socialize or learn from each other. Dissociated from experience, reason is independent of character qualities such as honesty or dishonesty. Self-reflexive reasoning loses its hold on reality.

What happened in the West as the Lutheran and Cartesian paradigms gained influence? Maritain’s answer is: split personalities. He selects Jean-Jacques Rousseau as the archetype of this modern dualism. Rousseau is famous for his “Social Contract,” in which he redefines natural morality. Rousseau was the first to proclaim, “’You must be yourself.’” He redefined sin as any attempt to bring your discords into unity. Every form imposed on the human soul is now a sacrilegious wrong against nature. Rousseau sets up a mirror image of Christian sanctity, its utter inversion. He rejects the Thomist “imperium,” by which the intelligence, moved by the will, orders the executive faculties to do what it has judged should be done.

Rousseau published his Confessions as a competing alternative to the Confessions of St. Augustine and told how he fathered five children with his housekeeper. Every time she gave birth to a baby, he told her to abandon the child at the foundling hospital. Meanwhile, he was writing books about the education of children and the proper design of society. By the way, this woman adored him and went around telling people he was a saint. He agreed with her and was as in love with himself as she was: “’I am convinced that of all men I have known in my life, none was better than I.’”

Rousseau is the modern type of the split personality in that he really believes in his own goodness, based on his ideology, even though his actions in no way correspond to what he claims to believe. His imaginary good self is just the opposite of his real self as demonstrated in his behavior. He is aware of his own inconsistencies without being bothered by the contradictions: “’If I had a more compelling illusion I should adopt that.’” Rousseau wrote contradictory works simultaneously, remarking that one or the other must succeed with the public. He knew and accepted his own hypocrisy with tranquil irresponsibility.

Rousseau promulgated a doctrine of absolute nonresistance to impulses. “Natural Goodness” is his alternative to the Christian state of grace. He hallows the denial of grace and instead savors the spirituality of sin, the flavor of the fruit of the knowledge of evil. He teaches us to take pleasure in our transgressiveness, to remake the ideal in our own image, and from this exalted vantage point to condemn any reality that differs from our personal sacredness. If reality does not conform to your dream, reality is wrong.

In addition to the myth of Natural Goodness, Rousseau also launched the myth that man is Born Free (the “lonely Savage in a forest” trope). Therefore any submission to authority is a corruption of original freedom. The Thomist view was that man is by nature a political animal, but Rousseau redefines human beings as inherently isolated (indeed, abandoned by their parents). Rousseau proclaims this state of isolation as a good thing: “’I shall need only myself to be happy.’”

And yet, Rousseau asserts that these happily isolated individuals agree to pass into a socialized condition through the Social Contract. After entering into the Social Contract, individuals have abdicated their natural rights. Each individual transfers his rights to the society and is absorbed into the social body. In this social state individuals no longer exist except as parts.

And then there is the myth of the General Will—a sort of political pantheism. Law no longer proceeds from reason but from numbers. It has no need to be just. Sovereignty derives not from God but from the mass of melded individuals. There is no more command to love God. To attain the good, we must reject restraints and refuse to do anything that feels like an effort. There is no original sin, and of course no hell, no accountability to God. There is no transgression, except against oneself: “’Supreme enjoyment is in satisfaction with oneself.’” Maritain calls Rousseau the first modernist priest, since he rejected faith in God and yet kept religiosity—a new religiosity of self-worship.

Maritain’s analysis of the disintegrating modern person in strange tension with society is eerily relevant to the convulsions of identity politics today. The centrifugal trends he identified a century ago are even more extreme now. Anyone looking for solutions to the dissolution of postmodern society will find a treasure trove of ideas in his Thomist perspective. Reaching back to a forgotten era of integrated Christian philosophy, Maritain retrieves concepts that restock the intellectual toolbox. He concludes: “It is heartbreaking to see so many intelligent creatures looking for liberty apart from truth and apart from love. They must then seek it in destruction; and they will not find it….The deliverance for which all men long is only gained…when love—a measureless love, for ‘the measure of loving God is to love Him without measure’—has made the creature one spirit with God.”