Genre

Audience

Adult

Author’s Worldview

Year Published

2017

Themes

Eugenics, anti-human experimentation, Embryos, IVF, abortion, Incarnation, imago Dei, personhood, theology of the body

Reviewed by

Courtney Guest Kim

Western utilitarian culture acts on the assumption that embryos have no inherent worth: they’re just the stuff from which a commodity is produced, namely, a child. But Christians have been opposing versions of this mentality from the days of Greco-Roman infanticide. In this tradition, Dr. Calum MacKellar, a Fellow with the Centre for Bioethics and Human Dignity at Trinity International University, Chicago brings to bear the witness of the Church, science and philosophy to defend human embryos against the notion that they are disposable clumps of cells. In The Image of God, Personhood and the Embryo, he synthesizes three topics that are not usually explained in relation to each other: embryology, theology and the definition of human personhood.

Subscribe to Our Email & Get Weekly Catholic Books for as little as $1

When does a human person begin to exist? Dr. MacKellar answers this question according to the doctrine of the imago Dei, man created in God’s image. St. Paul’s assertion that Christ is the “image of the invisible God” (Colossians 1:15) hearkens back to Genesis, where God deliberates with himself as he sets about making human beings: “Let us make mankind in our image.” The “us” represents the relational nature of God, a quality he also endows his creatures with. To be created in God’s image is to become a person in community. God creates freely, out of love, for the sake of the persons he brings into existence. From the beginning of this world, he designed humanity in such a way as to make possible the Incarnation, the historical moment when he entered into his own creation as one of us.

The Incarnation is the theological underpinning of each human being’s worth. At the moment in time when the Virgin Mary conceived, the Word of God took on humanity. An already existing divine Person started to exist as an extremely small and vulnerable human embryonic person. Christ’s incarnation as a human embryo at a particular moment in history bestows a sacred status on all human embryos. The Incarnation shows God’s valuing of the weak who have no one to speak for them—a theme which resonates throughout the Bible. The Word of God became involved in humanity, healing all those who approached him in faith.

The Church has always maintained that human persons in development reflect the divine image just as adults do. Embryos must reflect the divine image, if the Incarnation really took place as described in the Gospels. Since the Council of Constantinople in 381 A.D., the concept of “three hypostases in one ousia”—three persons in one being—became the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. Each Person of the Trinity is the Being of God, not just the Being in a certain role. The Council of Chalcedon, in 451 A.D. defined Jesus the Christ as “one person with two natures.” The historical Jesus was as fully body and soul as he was fully God and man. This trinitarian understanding includes the notion that God both transcends and is present in the world that he created from the sheer generosity of his love. He remains continuously involved in his creation and is immanent within it, sustaining its order. God made himself vulnerable to his creatures by limiting himself in order to endow us with freedom, even the freedom to attack him. God is indestructible, but to destroy a human being at any stage of existence is to attack the image of God. To destroy an embryo in particular is to attack Christ.

Beginning with Boethius’ description of a person as “individual substance,” the Church over time has refined its definition of the human person:

- A person is a distinct individual who maintains his or her identity through time, despite fluctuating attributes.

- A person is a unity of body and soul.

- A person differs from animals and objects in having potential for reason and free will.

- A person communes with others through relationships.

- A person is undivided in him or herself.

Subscribe to Our Email & Get Weekly Catholic Books for as little as $1

The Thomist principle operari sequitur esse means that our behavior and attributes flow out of who we essentially are. Attributes do not give rise to personhood, but personhood to attributes. This understanding is consistent with the original Jewish tradition, in which a person does not have a soul but is a soul. One does not have a body but is a body. Each of us consists of a whole body and a whole soul. There is a simultaneous origin and coexistence of the soul and the living body. Each person is worth the same as any other.

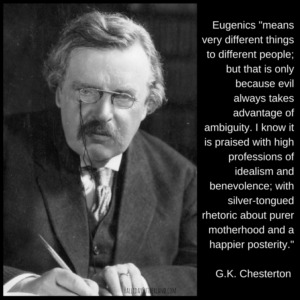

Over the course of several centuries, this Christian understanding of personhood has been increasingly challenged by substituting the “nature,” or attributes, the qualitative dimensions of personhood. In Western countries, this trend led to the redefinition of persons as self-conscious, rational and autonomous individuals. The person in his or her substantive otherness was slowly reduced to what the person could do. René Descartes’ famous phrase, “I think, therefore I am” was echoed by John Locke’s definition of personhood as “the ability to think, combined with self-consciousness.” Then David Hume suggested that personal identity consists of a series of experiences. Immanuel Kant came along with “practical reason” and “the will.” Secularists celebrate this “Enlightenment” for dissociating anthropology from theology.

Today, personhood is all about what you can do. This is called “performance theory,” and it says that you must qualify for personhood by demonstrating certain characteristics. It’s not enough to be human: you must manifest self-conscious rationality. You must demonstrate brain function to those who observe you. So, we find ourselves in a situation where not all human beings are persons anymore. Individuals lose their personhood as they lose their ability to perform. People with superior attributes—funny enough, the ones making the decisions—have greater personhood. From an atheist perspective, not just embryos but all human beings are just amalgamations of cells. No one has intrinsic moral value. The “gradualist approach” is this secular attitude to the moral status of human beings. Status increases or decreases with measurable attributes, so individuals are not equal in value. There is no longer anything precious in humanity itself.

So which stance is true?

From a biological perspective, an embryo is already an organism from the one-cell stage: the zygote. An organism is a thing that self-organizes. That’s how you can distinguish it from any other cell or group of cells. Syngamy is the process by which the two pronuclei, containing the chromosomes of the egg and sperm come together, as their separating membranes dissolve. This process of fertilization is complete within twenty-four hours. The resulting one-cell embryo (which immediately begins dividing into further cells) already has all the intrinsic properties needed to develop as a whole person—if you give it the chance. Although it is invisible to the naked eye, it is a living, organic whole with a unified, harmonious and dynamic constitution.

The embryo is resilient, but already by the four-cell stage it may not recover if you remove one of its cells. Until the eight-cell stage, one separated cell could potentially develop into a whole new embryo. This property of the cells is called totipotency. Up to the fourteen-day stage, an embryo can split into two or more cell clusters, which may develop separately and be born as twins or multiples. So a single zygote can give rise to genetically identical but distinct persons.

Individuality is compatible with divisibility. When an embryo spontaneously splits in two, what matters is that both before and after the separation, each is a distinct, whole organism. The manner in which an embryo comes to be is secondary to its existence. Each embryo is a complete organism that remains identifiable as itself throughout its life. By fourteen days after natural fertilization, implantation into the uterus of the mother is usually complete, and no such further splits can occur.

IVF (in vitro fertilization) embryos are usually implanted on the second or third day after fertilization. With IVF, for the first time in human history conception has been removed from the mother’s body to an outside location. IVF embryos have no legal status in the United States, where they are considered property. IVF embryos are screened for their genetic characteristics, and those rated inferior are routinely discarded. Even if they have no defects, extra unwanted embryos can be discarded as wastage or frozen in storage to be used later. Or, they can be donated to serve as specimens in experiments that will destroy them in more interesting ways. Instead of fulfilling their potential as human individuals, they will be sacrificed to biomedical research.

Some of this experimentation is producing new sorts of embryos, never before seen in the history of the world:

Parthenogenesis is a procedure which tricks an egg into becoming an embryo, as if it had been fertilized.

Pronuclear transfer generates children from several different individuals: such as a chromosomal mother, a chromosomal father, a partial egg mother and a sperm father.

A biparental, unisexual embryo is developed using the chromosomes of two sperm or two egg cells from two persons of the same sex.

A chimera is an embryo formed through the combination of early embryonic cells from one or more other embryos, including combinations of male and female embryos that result in entities that are part male and part female.

Human-nonhuman chimeric embryos are biological organisms that are made up of genetically distinct populations of human and animal cells.

Human-nonhuman true hybrid embryos are organisms in which all of the cells have both human and animal origins. These can be made by fertilizing a human ovum with animal sperm, or by fertilizing an animal ovum with human sperm. Since the zona pellucida of the ovum and the tip of the sperm are species specific, scientists get around the natural barriers to these combinations by introducing the sperm cell of one species directly into the egg of another species.

The United States is the country with the record for most barriers broken. In the U.S. there are no limits on biomedical companies doing embryologic research, as long as they are funded by private capital. Published results of experiments document that some types of embryos have so far not been observed to develop beyond early stages. Other researchers have deliberately destroyed embryos at a chosen stage, beyond which no documentation is available.

Against these practices, the Church—the whole Church throughout all history, in all denominations—asserts that only God is Creator. He alone can bring something out of nothing, and the organization of his universe is not just physical, but moral. Procreation is the participation of man and woman in the creative act of God, in order to bring new human beings into existence, according to laws that he designed for our good. Embryos should never be used for experiments or discarded as byproducts in the manufacture of children. They should not be sacrificed for other people’s benefit, health or happiness, even their parents’. Some embryonic human beings will never be known by anyone but God. But each of us in any case receives our worth only by being known by God. What matters is not what we look like, nor the length of time we spend as mortal bodies. What matters is that we exist at all, and that we exist in relationship with him. This is true even of human beings who lack rationality, such as embryos, Alzheimer’s patients, or head trauma victims. What is important is not that we are aware of ourselves, but that God is aware of and committed to us.

As examples of the imago Dei, each of us is endowed with both moral status and responsibility. We stand in relation to our Creator, dependent on and confronted by but also mirroring his image. Science, which is the study of the physical universe cannot demonstrate moral value. Value is discerned by beliefs, not by physical measurements. Moral authority comes from the Creator, not the created. Although we are not morally accountable for processes over which we have no control, we are certainly accountable to our Creator for our deliberate actions.

If you can read this, you are standing as a morally responsible agent before God. Do you want to find out more about what the Church has said on this topic, across various denominations, over the past two millenia? Do you want to delve into the details of embryology and the experimentation that is being done? Do you want to reflect on the philosophical questions surrounding human personhood? The Image of God, Personhood, and the Embryo has done the work for you of assembling the relevant information, presented in eight clear chapters backed up with nearly a thousand scholarly references.

“Those who are committed to defending human dignity can find in the Christian faith the deepest reasons for this commitment. How wonderful is the certainty that each human life is not adrift in the midst of hopeless chaos!” [2015 Laudato Si, Pope Francis]

“Human life is sacred from its very beginning, since from conception it is ensouled existence. As such, it is personal existence, created in the image of God and endowed with a sanctity that destines it for eternal life.” [2001 Synod of Bishops of the Orthodox Church of America]

“This Assembly regards the destruction by parents of their own offspring, before birth, with abhorrence, as a crime against God and against nature.” [1869 General Assembly, Presbyterian Church in the USA]

“For it was you who formed my inward parts; you knit me together in my mother’s womb.” [Psalm 139:13]

“Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.” [Matthew 25:40]

Join Here for FREE to Never Miss a Deal

Find new favorites & Support Catholic Authors